What You See is What You Get. Sometimes.

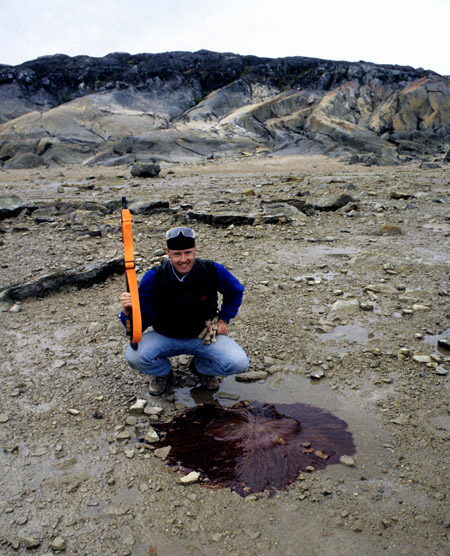

Norm Aime examines a large dead example of Cyanea capillata (the lion’s mane jellyfish) on the shore of Hudson Bay near Churchill, Manitoba. (photo © Dave Rudkin, Royal Ontario Museum)

It is a common error of logic to think that the rest of the universe will conform to our modest experience of our own little piece of the world. We see this sort of faulty generalization all the time in discussions of topics like evolution and global warming; it is the perception that “if I haven’t seen it with my own eyes, then it cannot be true.”

As scientists, paleontologists should be less prone to this sort of error than some other people, and I think in general we are good at examining all the available evidence, digging through the published literature to determine the most accurate answer to a particular question. This doesn’t necessarily hold true, however, when we consider issues that are barely touched on in the literature: when we are looking at fossils and situations that are poorly documented anywhere in the world. When we are considering these, we tend to be like anyone else and fall back on our personal experience.

I started thinking about this last fall, when I was in Europe visiting various collections with my colleague Whitey Hagadorn, and having discussions with other scientists about ideas on fossil jellyfish. The fossilization of jellyfish is a very weird and rare phenomenon: the few decent medusa-bearing deposits are widely dispersed in space and geological time, and fossil jellies are mostly not well documented in the modern scientific literature. Since the deposits are spread out, those people who study jellyfish and related fossils have generally only looked in detail at specimens from one particular deposit.

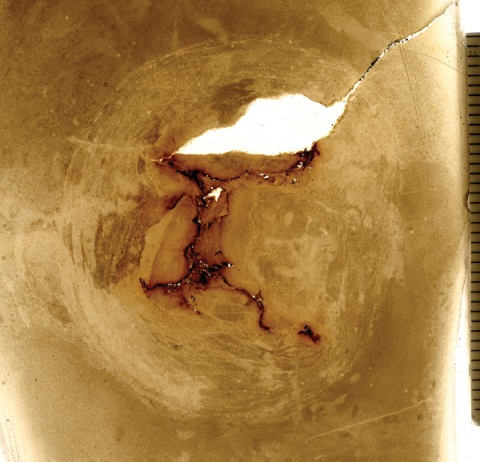

Transverse thin section through one of the William Lake medusae, in which canals are preserved as “rusty” orange features (The Manitoba Museum, specimen I-4262; scale is in millimetres)

As the fossilization of medusae is such a rare thing, it might be natural to assume that it could only happen in one or a couple of ways. I find it fascinating that this is, actually, not the case. Having spent most of my “jelly time” examining material from the Ordovician William Lake site in Manitoba, I am used to jellies of small to medium size that seem to have fossilized from the inside out, so that canals, gonads, and other internal features are preserved, while more peripheral features such as tentacles and bell surfaces are virtually absent.

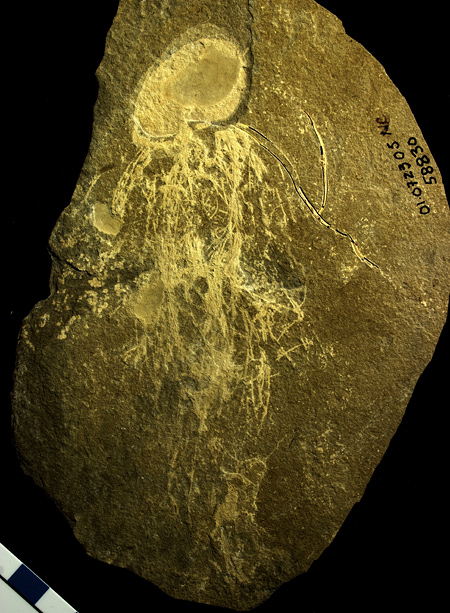

When I started looking at jellies from other deposits, I was surprised to find that the medusae in the Carboniferous Mazon Creek of Illinois are almost the reverse, having been preserved from the outside so that we see tentacles and other external features but almost no internal characters. The jellyfish in the Jurassic Solnhofen Formation of Germany mostly preserve internal structures, but the fossils are typically very large and they exhibit features such as muscles, which cannot be seen in William Lake specimens. As Whitey and I continue studying specimens from other deposits, we see that each bears a distinctive preservational signature; each represents a different set of strange and rare environmental conditions.

Fossilized from the outside in: a specimen of the Carboniferous box jellyfish (cubozoan) Anthracomedusa turnbulli, from the Mazon Creek biota, shows a bell surrounded by abundant tentacles. (specimen in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum)

Even in this modern age, it seems that there are still more things in Heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy. And the more I look at these things, the more strange they seem to become. Even if I have long accepted that the preservation of fossils in one place will not be duplicated in others, I somehow didn’t appreciate until very recently just how lucky I am to be working on our particular deposits in central and northern Manitoba.

One of the major issues with soft-tissue preservation is that we are dealing with the dead remains of creatures that have been through the taphonomic mill, subjected to physical processes and to some subset of the fabulous range of microbial putrefactions and fermentations. Since the bodies are never truly pristine, one needs to see as much fine detail as possible to ascertain what particular preserved features might represent, to extract original morphology from the taphonomic overprint. The fossils from William Lake do not have much colour or contrast, but the preservation of detail is quite remarkable. The superb preservation in very fine-grained dolomudstone means that, no matter how closely I examine one of these fossils, there are always things to find. Using a really good microscope, I actually run out of magnification before I run out of features to examine.

Passing through the taphonomic mill: a somewhat degraded example of Cyanea capillata on the tidal flat, Island of Colonsay, Scotland

Since the other soft-tissue fossils I regularly spend time with, from Airport Cove, show comparable preservation, I really expected the fossils in other unusual sites to be similar in their fine detail. But what I have discovered over and over, looking at specimens of various groups from places like Cat Head and Solnhofen, is that it is often a case of “what you see is what you get”. The fossils may look beautiful and appear to show a lot of features, but placing them under a microscope shows . . . nothing. Or at least, nothing beyond what can be seen with the naked eye. In fact, in many instances even a hand lens does not show anything beyond what you have already made out from two feet away.

Considering the various fossils and deposits, I am reminded of my old days as a graduate student, when we used to do our own darkroom work, processing film and printing photographs. Working with black and white film, I learned first-hand that some film types may look good to the naked eye, but that when you do enlargements you may rapidly run into issues with film grain, which obscures finer detail. Other film though, such as Kodak’s T-MAX, has tremendously fine grain, so fine that it can be very hard to view the grain when using a fine focus device during the printing process. With a film like that, you can enlarge from just a small area of the negative if you wish.

Sadly, many enigmatic and obscure fossils are of the non-T-MAX variety. Most recently, I have been trying to understand a slab from the Carboniferous Bear Gulch Limestone of Montana, a specimen loaned by the Royal Ontario Museum because it contains a curious jellyfish-like fossil. To the naked eye it is a very promising piece, since it appears to contain a body and numerous elongate tentacle-like structures. I have been examining and photographing the heck out of it, trying various cameras and microscopes, and using different lighting such as double-polarized illumination and an ultraviolet light source. Yet the slab refuses to yield any fresh secrets beyond those that could be seen when we unwrapped it from the box in which it was shipped.

If you are trying to make sense of an enigmatic fossil, I hope you don’t discover that its preservation is a case of “what you see is what you get”. If that is so, you’d might as well drop the project and move on to something else; there will never be enough information there for you to reach a reasonable conclusion. As I have realized after a month or so contemplating that Bear Gulch specimen . . . but still . . . maybe if I just try a few other photographic techniques . . . ?

© Graham Young, 2014

Excellent article Graham! I would like to suggest trying to image the ROM jellyfish under infrared wavelengths through 680nm- 720nm IR filter ( you would need a converted IR camera ) to see if other features stand out…. just a thought….. also as you have already mention variable cross polarized light works well. PL 🙂

Thanks Peter, those are good thoughts!

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article – the jellies are fascinating creatures. I’ve go to get busy and rephotograph the interesting fossil I have from the Williamsville Waterlime, Bertie Group.

Sam, thank you for the comment. I would love to see what you are finding.

Graham: I’m going to try to add photos: Williamsville Waterlime, Bertie Group. How do I add photos?

Sam, I’m not sure if you can add photos within a comment on here. If you can’t manage it, and you think they are relevant, maybe e-mail me the appropriate ones and I can either add them as a short follow-up post, or we can discuss whether there is the potential for a research collaboration.

Hi Graham: Here are some Mazon Creek images of Jellyfish imaged with IR at 720nm: see link https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=oa.664611053577345&type=1

Thank you, Peter.