Skeleton Surfeit?

La Galerie de paléontologie et d’anatomie comparée, Part 4

I have been struck by the volume of ongoing interest in my post a few months back about the comparative anatomy exhibits at the Galerie de paléontologie et d’anatomie comparée in Paris. This museum does have an overwhelming quantity of superb material on exhibit, and looking back through my photos I realized that there are many good ones that I had not posted.

Groups such as the whales and ungulates are heavily represented in this gallery, and when I wrote that post I wanted to cover as many groups as possible, so I left out a lot. In case you might be interested to see more photos of the place, here is a selection of those remaining …

This armadillo (Dasypus) is mounted to show the relationship between its skeleton and armoured "shell."

Valaste!

♦

Valaste may well be the most attractive thing to ever come out of a drainage ditch.

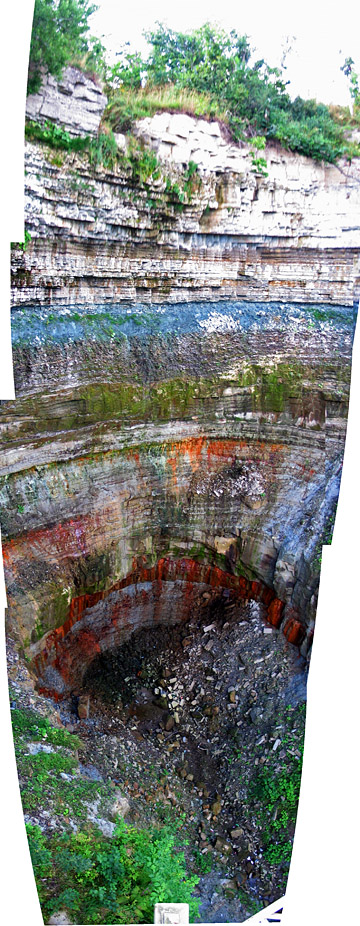

It was born two hundred years ago, with a plan to drain the fields of a manor house in northeastern Estonia. A large ditch, seven kilometres in length, was dug to carry water from the fields to the edge of the Baltic Klint, the limestone cliff that runs all the way from Russia to Sweden beside and beneath the Baltic Sea. Where the ditch meets the cliff, it has formed the highest waterfall in the Baltic states. During the rainy season, water can fall as far as 30 metres to the gorge below (the height varies, depending how much talus has gathered).

Since scenic beauty spots are rare in northeastern Estonia, the authorities capitalized on this unlikely place by building a viewing platform in the 1990s. This is not only a boon to tourism; it is also a great kindness to geologists. Our group visited on an August morning, trooping down from the parking lot above. In this dry weather there was almost no water flowing, but this permitted us to view an even more exciting outcome of the drainage project: it has cleaned and scoured the cliff wall, exposing a spectacular succession of Cambrian and Ordovician sedimentary rocks.

Walking along the catwalk, the foreign visitor is struck by the large number of padlocks attached to the railing. Why are these here?

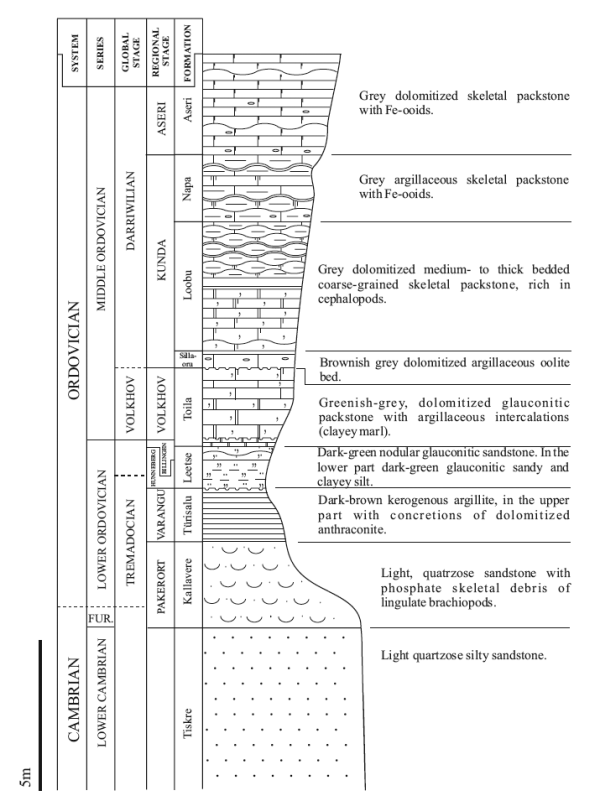

The rocks include sandstones, argillites, oolites, and packstones (there is a photo of the full section here and near the bottom of this post). Some of the units are rich in marine fossils, such as cephalopods and brachiopods. The colour variations are striking, reflecting the changing environmental conditions in those seas of half a billion years ago. According to the published charts, the red rock down low is a pyrite-rich sandstone (Lower Cambrian Tiskre Formation), while the blue unit high up is a glauconitic sandstone (Floian [Ordovician] Leetse Formation). Just below the blue is a dark organic-rich argillite. The green intervals show the growth of moss or algae, where water flows out of the more permeable units. [these colour explanations were improved by my friend Helje Pärnaste, but any errors still present are entirely my own]

Looking more closely, you realize that every padlock has words etched on it. Most of these are in Russian, and they are the names of courting couples or lovers (much of this end of Estonia is inhabited by ethnic Russians). Apparently it is a local habit for couples to have their names etched onto a padlock. They then lock it onto the railing, and throw the key into the abyss to symbolize their love.

My question is: what happens if the relationship falls apart? Does one of them just go in at night with a hacksaw and cut away the padlock, or are they required to jump over the rail and retrieve the key?

Unfortunately it is not possible to get close to the cliff here, not without some serious climbing gear. We had to content ourselves with a broad and very general overview of the colourful geology on this, our first morning in Estonia. There would be many interesting sites to visit in the coming week of touring quarries and shorelines, so we would not experience any shortage of rocks and fossils during this trip! Right now, there was time to breathe the cool Baltic air after a week of St. Petersburg smog, and, perhaps, time to contemplate local customs.

Note (added March 9): I have corrected the explanation of unit colours with the kind help of my friend Helje Pärnaste in Tallinn, who also tells me that, “You have been lucky to see that view to such condensed section from Lower Cambrian to the Mid-Darriwilian. These stairs and the platform are closed now, and perhaps for ever. It became too unstable during eleven years because of its wet sandy base, and there is not now money for restoration.” This is sad; it is such a splendid spot.

I also thank Olle Hints and Mari-Ann Mõtus for doing such a wonderful job of leading our field excursion in 2007.

References:

Mõtus, Mari-Ann and Hints, Olle (eds.). 2007. Excursion B2: Lower Paleozoic geology and corals of Estonia. 10th International Symposium on Fossil Cnidaria and Porifera. 64 p.

Tinn, O. Stop 10, Valaste Waterfall, p. 137-138. WOGOGOB-2004, 8th Meeting on the Working group on the Ordovician Geology of Baltoscandia. May 13-18, 2004, Tallinn and Tartu, Estonia.

Not all waterfalls on the Baltic Klint were dry when we were in Estonia. This is a photo composite of Jägala Juga, the highest natural waterfall in the region.

© Graham Young, 2011

Bloody Bears and Humans

I have spent quite a bit of time in the “near north” – not the high Arctic, but still far enough north that I have seen arctic foxes, caribou, ptarmigan, arctic hares, belugas, and, of course, polar bears. And this has not been from the comfort of a tour vehicle; we have generally been on foot, out on the open land.

There have been several occasions when we have had to move out of an area quickly because a bear suddenly appeared over the bluff, and other times when a bear has watched us for quite some time from a (relatively) safe distance, as though he was bored and wanted us to provide entertainment. They have been close enough for us to get the shotgun ready and pull the cracker pistol out of its holster. Still, I have never had a really scary encounter with one of these creatures, and for that I am grateful.

Recently, seeing photos of bears covered with blood from their prey, I was reminded of a story once told to me by a man who has lived near Churchill for many years. He has probably had more bear encounters than most bears have had seal dinners, but of all of those encounters, he said that only one of them was really frightening.

Bear meets humans at Akimiski Island, James Bay. At Akimiski the humans are caged in their field camp behind a security fence, while the bears roam freely outside (David Rudkin, Royal Ontario Museum)

It was autumn and there had been snow but there wasn’t yet ice on the bay, so the bears were plentiful around town. The large male bear surprised him around the corner of his house. This bear was well-fed and had blood all over its fur, at a time when it could not have caught a seal in months. The only possible explanation was that it was a cannibal; it had become fat and bloody because it ate other bears. And because it was an outcast (and a psychopath, if such things exist among polar bears), it had even less respect for humans than the average bear has. It kept coming back, it seemed devious and evil, and eventually someone had to shoot it.

I find it hard to shake the image of that bear; perhaps the one positive aspect of the story is that in the polar bear’s world, the psychopaths are readily identifiable. It would certainly be easier for society if human psychopaths actually LOOKED bloody. While we do have laws that generally prevent the sort of treatment of other people that this bear was meting out on other bears, our treatment of some bears and many other relatively sentient animals still leaves a lot to be desired. Are we, in a sense, in the grip of a group mental disorder?

This young bear and a sibling were tethered in a picturesque part of St. Petersburg in 2007. The owner was charging tourists and wedding parties for the privilege of having their picture taken with a true "symbol of Russia." What are the chances that these bears have survived to adulthood? And under what conditions?

© Graham Young, 2011

Life’s Dusty Attic

La Galerie de paléontologie et d’anatomie comparée, Part 3

We climb yet another flight of stairs. Up here, the heat of the Paris summer is utterly stifling – it is still and humid, and we are becoming drenched. The age of the museum surrounds us, in the typewritten labels, the paint peeling from the walls, and the dust motes hanging in the sunlight. But it is a treasure house. I feel a bit like I am Howard Carter, entering the tomb of Tutankhamun. There is a sense of discovery, of marvellous objects undisturbed by a century of of change and “progress.”

Each corner of the mezzanine is "anchored" by a superb specimen. This is a painstakingly prepared cluster of irregular echinoids (similar to sand dollars).

I have to see it all, drink it in, absorb it through my eyes. There are so many fossils here, and yet there are not enough for me! The family do not share my affliction of paleolunacy, but they accept that there is little they can do about it. They wait patiently in the air-conditioned space near the end staircase, and I am left alone in the heat, to explore the wonderful specimens in solitary revery. Here, a cluster of fossil pectens of unmatched quality and size. There, models of microfossils, hand-carved from limestone in the nineteenth century. Farther along, a huge collection of creatures that lived on some warm Paleozoic reef. This is the attic of life, holding much of the deep and fascinating story.

If you want to see more of this Paris museum, please take a look at Ghost Giants, about the fossil vertebrates, and Skeleton Squadron, about the modern vertebrates.

Whispering Past, the Graveyard

When I was a boy, one of our favourite summer outings was to the camp of our relatives on Grand Lake, New Brunswick (a “camp” in the Maritimes is what other Canadians call a “cottage,” or what some of the rest of you might call a “cabin”). Once there, we would swim in the lake or maybe pick strawberries or raspberries in the old fields, evidence of the farms that once occupied the sandy soil of this area. And we would take long walks down the gravel Scotchtown road to the Thoroughfare, where the rippling Grand Lake Meadows grade gently into the blue of the lake. The area was the ghost of a late eighteenth century settlement, with a few dispersed farmhouses, summer vacation places, forest, and a well-tended little cemetery.

My family were all interested in the past (my father was an historian), and we would always stop at the cemetery to read the gravestones. If we travelled elsewhere, we would do the same thing: walk in cemeteries and read the inscriptions. We were taught to be respectful, not yelling and running, and never stepping on the graves. Unlike my own children, I never found graveyards at all creepy, probably because we spent so much time visiting them. At 10, I did find it boring to spend more than three minutes reading gravestones, but 40 years later the experience has stuck with me.

As a kid I'm sure that I WOULD have found this place creepy: a "street" of tombs in the city of the dead at Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

I realized this a few weeks back, as I sat in a graduate seminar discussing the lives and interactions of ancient animals. Jeff, the student, was describing a book chapter on evolutionary strategies of species, and he made a statement that really caught my attention. He said, quoting the textbook, that humans belong to the category of organisms that have the strategy of producing relatively few offspring, because the great majority of us live to be mature adults. My immense experience on the graveyard shift told me that, while humans do produce relatively few offspring, through most of the history of our species it has not been an expectation that the great majority of babies will live to a ripe old age.

Medusae on the Road

Getting Jelly out of Stone:

Getting Jelly out of Stone:

Presentation at Brandon University, February 11th

In about three weeks I will be travelling to Brandon University, to make a presentation as part of their Darwin Days events. I will be talking about the fossil record of jellyfish, and how it relates to modern ideas on the evolutionary relationships of the various medusan groups. The presentation is at 3 pm, if you are in the Brandon area and interested in this subject.

When I had to come up with a title for the talk, I thought that Getting Jelly out of Stone: The Fossil Record and Evolution of Cnidarian Medusae seemed appropriate. The “out of stone” was with reference to the common saying that “it is like getting blood out of a stone,” since fossil jellyfish are so difficult to find and to interpret. It was only later that I realized that it might also be seen as a rather weak pun on the location for Yogi Bear. Oh well.

(the images are “negatives” of jellyfish on exhibit at the Vancouver Aquarium)

© Graham Young, 2011

Ghost Giants

La Galerie de paléontologie et d’anatomie comparée, Part 2

A couple of months ago, I posted photos of the modern vertebrates at the Galerie de paléontologie et d’anatomie comparée, the wonderful museum that opened for the 1900 Paris world’s fair, with a promise that there would be follow-up pieces on the paleontological exhibits. As it is now Christmas, this seemed like an appropriate time to open up the next section of this candy box. Paleontology occupies both the second level and a gallery/mezzanine above, so I thought I would just present the second level at the moment, particularly since the spaces approximately divide the vertebrate and invertebrate fossils.

This replica skull of the Devonian arthrodire (fish) Dunkleosteus may look familiar to some of you. It is identical to casts on display in many other museums, including the Manitoba Museum.

Most galleries of fossil land vertebrates are, let’s face it, dominated by the dinosaur skeletons. For some reason, this Paris museum is different. I’m sure that the dinosaurs are big, since some of them seem to be identical to casts that have looked very impressive in other settings. But they don’t look all that huge here. Their bulk does not impose upon or overwhelm you, and I’m sure that a lot of this comes down to the space in which they are exhibited. The gallery seems like an optical illusion to me: its proportions are such that it does not feel huge, and yet it clearly dwarfs the skeletons contained within.

Recognizing Fossil Jellyfish

- Octomedusa pieckorum is a “classic” fossil jellyfish from the Upper Carboniferous Mazon Creek (Carbondale Formation) of Illinois. (Royal Ontario Museum, ROM 47540; scale on right is in centimetres)

After my post on the Ontario Silurian blobs, I received several comments along the lines of “how do you go about recognizing fossil jellyfish, anyway?” Fortunately for those who asked this question, my friend Whitey Hagadorn and I have just published a paper on the jellyfish fossil record as it is currently understood. I thought it would be worth paraphrasing the part of the paper related to jellyfish recognition here, as a guide to those who think they might have found fossil jellies. If you want to read the entire paper, or look at the references on the subject, a pdf can be found here.

Jellyfish, or medusae, include three major groups of cnidarians: scyphozoans (“true jellyfish”), hydrozoan medusae, and cubozoans (box jellies). In the modern world, jellyfish are widespread in the oceans, as are their cnidarian cousins the corals. But in comparison with what we see today, the fossil record is hugely biased toward those forms that have hard skeletons. Jellyfish are abundant creatures that often occur in immense numbers during certain seasons, but they are remarkably rare as fossils: there are only a few well documented occurrences in the entire fossil record.

Searching for Fossils in Manitoba’s Limestones

For the past couple of days, I have been scrambling to put together a presentation on fossil hunting in Manitoba’s limestones for a public open house session at the Manitoba Mining and Minerals Convention. If you are in the Winnipeg area, you might want to check out this session on Saturday morning, which includes several presentations on geological and paleontological topics.

If you don’t want to chase down the link, here is the abstract of the talk:

A significant proportion of Manitoba is underlain by carbonate bedrock that is often rich in fossils. In the south, limestones and dolostones occur along the margin of the ancient Williston Basin, from Winnipeg north along the lakes to the Grand Rapids Uplands and the Cranberry Portage area. These rocks, dating from the Ordovician to Devonian periods, are about 450 to 370 million years old. In the north, equivalent rocks occur in the Hudson Bay Basin, and are well known from Churchill to the Nelson River. All of the fossils in these rocks represent sea life. During this time, Manitoba was at or near the equator. Sea level was often very high, so that warm seas covered much of what is now land. Fossils found here include many groups of marine organisms, such as corals, brachiopods (lamp shells), trilobites, receptaculitids (“sunflower corals”), and nautiloid cephalopods. Other fossils, such as fishes and seaweeds, are much rarer and only occur at certain sites. All of the fossil species in these rocks are extinct, although some of them have living relatives. This presentation will include brief explanations of some of the fossil groups, describe where they can be found, and suggest preferred collecting techniques.

Linear Humans in a Complex Landscape

Last week, I was scheduled to fly to Denver during, as it turns out, the most intense storm ever recorded in the midcontinent of North America. Our flight was cancelled because the wind-driven weather had apparently damaged some control systems as the plane sat on the tarmac over night. All plans had to be shuffled and adjusted, and I eventually arrived in Denver 12 hours late.

It seemed to me that this was a classic example of a linear human schedule meeting a complex natural event. Whenever this sort of thing happens (and I have seen my share of flight cancellations), people’s reactions are always interesting to observe. Some of them stolidly take it in stride. Others sit back, observe, and take quick advantage of the first opportunity to re-book and move forward. But many, perhaps a solid third, get upset, stressed, and confused.

Subdivisions form tidy patterns on the outskirts of Denver. This photo and the subsequent ones are ordered to provide an aerial view of my return flight from Denver to Winnipeg, in the clear weather that followed the storm.

I was talking to the fellow beside me in the queue, and his reaction was, “How can this happen? How can the airline do this to us? Why are they messing up the schedule?”

He had, apparently, never had experience with calamitous natural events, and thought that it was some fault on the part of the airline that was keeping him from getting to his business destination as he had carefully planned.

This caused me to think about human nature, and how it relates to nature itself. Most civilized people are accustomed to order, we like to organize the world, and we tend to think that we can understand things by classifying and categorizing them. Sometimes this can work very well: so much scientific progress has come from classifying organisms and patterns, but good classifications only come when we learn to appreciate and try to understand complexity.