A Provenance Problem

Whale Cove, Grand Manan Island, New Brunswick

The inner end of Whale Cove is defined by an immense barrier bar, separating the lagoonal barachois from open waters of the bay. Walking along the bar on an unseasonally hot summer day, you are struck by the fact that many of its constituent stones are geologically rather similar. Unlike some beaches elsewhere on Grand Manan, which contain a great diversity of rock types, the bar is largely composed of pebbles and cobbles of basalt.

The source of much of the basalt in the Whale Cove bar is easily determined. Northward, either side of the bay’s mouth is lined with cliffs. Ashburton Head on the western horizon is particularly impressive, and in front of it are the layered flows of the Seven Days Work. Basalt, almost as far as the eye can see! These rocks are all part of the uppermost Triassic Dark Harbour Basalt.

Much of the basalt in the bar is of a mid grey colour. Wet stones by the sea look black, but in the midday sun the round cobbles higher on the bar are bright and pale. The beachcomber’s eye is drawn to any that stand out from the background grey: each occasional piece of white quartz or pink granite is picked up and examined.

What You See is What You Get. Sometimes.

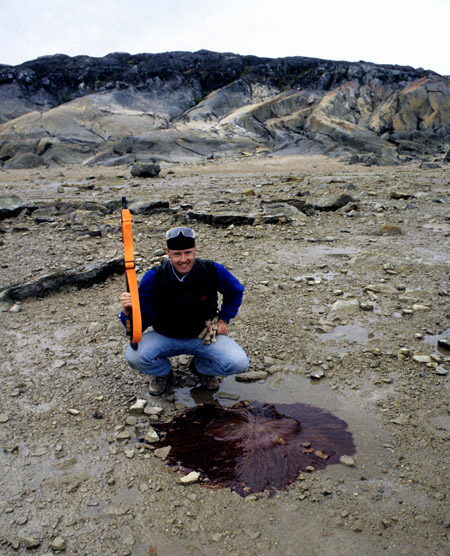

Norm Aime examines a large dead example of Cyanea capillata (the lion’s mane jellyfish) on the shore of Hudson Bay near Churchill, Manitoba. (photo © Dave Rudkin, Royal Ontario Museum)

It is a common error of logic to think that the rest of the universe will conform to our modest experience of our own little piece of the world. We see this sort of faulty generalization all the time in discussions of topics like evolution and global warming; it is the perception that “if I haven’t seen it with my own eyes, then it cannot be true.”

As scientists, paleontologists should be less prone to this sort of error than some other people, and I think in general we are good at examining all the available evidence, digging through the published literature to determine the most accurate answer to a particular question. This doesn’t necessarily hold true, however, when we consider issues that are barely touched on in the literature: when we are looking at fossils and situations that are poorly documented anywhere in the world. When we are considering these, we tend to be like anyone else and fall back on our personal experience. Read more…

Dead Zoo. Dead Zoons. Zounds!

The city of Dublin emanates a shabby charm. Much of the city centre has been beautifully renovated, yet the overall impression is of a once-elegant town that saw its prime sometime before Irish independence was achieved. Or maybe it is just a place that has its corners rubbed off quickly by the rough-and-tumble of life, its paintwork scuffed and doorways chipped by too many stonking Saturday nights.

Every case in the museum is packed full of creatures. These are small carnivores in the upper gallery (mostly mustelids, by the look of them).

The impression of a distant grand past is also evident as you step into Dublin’s public buildings. Just off Merrion Square, beside the Dáil (the Irish Parliament), stands the National Museum of Natural History. Though not constructed on the scale of its French equivalent, this institution similarly preserves the idea of the natural history museum as the repository of biological variety and morphological complexity.

You enter past the shop and the trio of splendid Irish elk (two antlered males, with a female to the left).

I will not attempt a detailed description and discussion of the Irish museum, since that was done twenty years ago by Stephen Jay Gould, in inimitable erudite fashion. As Gould pointed out, although the museum gives the appearance of a place frozen in time, it has in fact evolved and changed over the century-and-a-half since it was opened in 1857. But the changes have respected its initial intention, which was to exhibit the zoological diversity of Ireland and the wider world. Read more…

Guidebook: The Ordovician-Silurian Boundary in the Williston Basin

The field trip group visits roadcut exposure of the famous t-marker, in the Grand Rapids Uplands. The t-marker (mostly represented by the red layer in this image) is associated with the HICE (Hirnantian Isotopic Carbon Excursion), indicative of the time interval just before the Ordovician-Silurian boundary.

The last few months have been a bit of a blur, with many travels fitted into the summer and autumn interval. The prior months were a blur of a different sort, as a group of Winnipeg geologists scrambled to assemble the essential components of GAC-MAC Winnipeg 2013, the annual meeting for Canadian geoscientists. In addition to a variety of presentation sessions (including one I wrote about here a few months back), there were also several social functions, and some well-attended field trips. The field trip guidebooks have recently received online publication, and free downloads can be found here. Read more…

After Burn

One interesting sidebar to our annual research trips to the Grand Rapids Uplands is that we have been able to observe the slow decay of dead trees and regeneration of vegetation following the massive Norris Lake fire. This conflagration, in late May of 2008, burned 53,000 hectares of forest, including large areas adjacent to Highway 6 north of Grand Rapids. It turns out that the fire was started accidentally by students on an ecological program.

We were actually in the area in 2008 on the day the fire began, and I posted some fire and immediately-post-fire images a couple of years later, following those up again with some 2011 sunset shots. This September’s visit seemed like a good time to document the further regeneration, as the jack pine seedlings were a beautiful bright green against the autumn leaves, buff dolostone, and blackened trunks. Read more…

Travelling Hopefully

To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive.

– Robert Louis Stevenson

I seem to have spent most of October travelling rather hopefully. This hope was well-founded, as it turned out to be a very pleasant and productive trip, resulting in more than a few epiphanies about fossils and museums. Between work and pleasure I managed to cover a substantial swath of northern Europe, from Dublin to Stockholm to southeast Germany. About a third of the way into the trip I paid a visit to Dunster Castle, England, a place I had previously visited some 47 years ago. This brought to mind a series of events that occurred slightly after that earlier trip, when my family had returned to our regular life in Fredericton, New Brunswick.

Somewhere in the middle of Grade 3, the teacher, Miss A______, asked us to each paint a picture depicting an occupation we thought we would like to have when we grew up. So kids set to with their brushes and paint, showing what they might look like as a doctor or truck driver, or a nurse or secretary (this was 1967, so gender roles were very traditional).

My painting showed a figure in a tramp-like brown jacket and broad-brimmed hat, carrying a pack and grasping a walking stick as he strode down a road passing through green fields, with a hilltop castle in the background. When Miss A______ asked me to explain what occupation this depicted, I told her that it showed me as a “traveller”.

Being a practically-minded teacher in the Canadian Maritimes, she pressed me for a more rational explanation. Would I perhaps be a salesman, driving from town to town? Would I be in the military, or maybe drive a truck? Nobody made a living just by being a “traveller”! Read more…

Dublin Bay Dusk

Sandymount Strand on Dublin Bay is a difficult place to comprehend. Depending on how you approach it and where you look, it may tell you many different sorts of stories. Scanning southward along the shore, you will see a line of pleasant water-view homes, the edge of a city suburb. To the north is an industrial landscape, from the tall chimneys of the Poolbeg Generating Station to the cranes of Dublin Port.

As I walked along the seawall at dusk and low tide, I was surprised by the sheer number of runners and walkers on the firm sand immediately below me. To the locals, this is clearly a place of recreation. Others might contemplate it in the context of the long history of human settlement in the Dublin area, or maybe consider its literary significance as a setting for James Joyce’s Ulysses. Read more…

Found in a Quarry

People sometimes ask whether we need to protect ourselves from wild animals when we do fieldwork in remote northern areas. Sure, we carry shotguns for protection against polar bears when we are in the Hudson Bay Lowlands, and I have been known to carry pepper spray in case we meet black bears in boreal forest areas, or feral dogs close to farms. But the fact is that bears, coyotes, dogs, and wolves do not worry me all that much. I am more concerned about encounters in remote places with that most unpredictable of mammals: Homo sapiens.

I have to say that we have been very lucky with the kind, pleasant, interested people we meet as we tour around central and northern Manitoba. Nevertheless, when we are out there we do recognize that there is little backup other than our colleagues and their perceptions and reflexes. And though I have never had any outstandingly weird encounters with people in remote places, in my work in the city I have occasionally had dealings with some very strange individuals, so I know that they do exist. Read more…

Happy Snail Trails

Along the shores of the Bay of Fundy, the molluscs are so common below high tide mark that it is often hard to avoid stepping on them. Everywhere you go are periwinkles, mussels, and whelks.

On the average sunny day, you may not realize that molluscs are probably almost as abundant in places far above the shoreline. Walk under the trees on a misty morning, though, and you will see that the woods are full of snails. These gastropods, and their slug cousins, are wonderfully adapted to the humid Acadian Coastal Forest.

These photos are from a stroll between Red Point and The Anchorage, along the seaward side of Grand Manan Island, New Brunswick.

Index Trace Fossils of the Anthropocene

When I visit a city, I suspect that I sometimes look quite eccentric. Although I take in the usual tourist sites, I can also often be seen with my nose close to the wall of a stone building, or crawling around as I examine some small ground-level feature. This “insane” behaviour is, of course, driven by my interest in things geological. The average modern city is chock-a-block with diverse geological features, many of them originating from other parts of the world.

So there I was in Halifax last week, spending a few minutes walking around the town’s charming old centre. Imagine my delight when I saw this section of sidewalk ahead of me, illuminated by the low-angle light of the afternoon sun:

The non-dinosaur avian footprints had presumably been made by a pigeon (or two pigeons) while the concrete was still wet. The lovely preservation of these tracks started me thinking about what might happen to them in the future. Concrete is a tremendously durable material, effectively a human-made stone. If by some chance this sidewalk happened to be preserved for millennia, perhaps buried in sediment and later exhumed, would the pigeon footprints then be trace fossils? Can a trace fossil be preserved in a man-made material, as opposed to a natural one? (FYI, a trace fossil is the preserved record of the activity of an organism) Read more…