What Geologists Share: Fieldwork and the Four Dimensions

If you visit this page occasionally, you will have noticed that I have posted very little since last spring. This interval correlates rather precisely with my term as President of the Geological Association of Canada. I have discovered that it really isn’t possible to be both an active blogger and an active officer of a national organization, and since the term of the president is just one year, I have been focused on that. As president, I am at least able to write articles for the GAC’s member newsletter, Geolog; this piece is reprinted here by permission.*

A few weeks back, during the golden days of early autumn, I did some collaborative field research in southwest Manitoba with colleagues from the Manitoba Museum. Spending field time with people from other disciplines, I began to consider our different thought patterns, patterns that have developed as a result of experience and training.

The zoologist was driving our van, but he was constantly scanning around for creatures as he drove. He could recognize the species and gender of a bird in flight before I could even see the bird, and he counted dozens of red-tailed hawks during a morning where I noticed maybe four of them. He detoured around snakes on the road and then stopped to ascertain their species, age, and sex.

At a prehistoric bison kill site, the archaeologists could talk about the season of a hunt hundreds of years ago. They could envision the behaviour of people who drove the bison over a ridge and into a kill zone in the low wet rushes. We could see bits of bone everywhere, but they could find tools, know how the tools were made, and understand how the people were living and what resources they used. To me, it seemed like each of these non-geologist experts had their own “super power,” a quality that was beyond the ability of mere mortals.

As time progressed, I realized that we geologists also have our own super power. As we looked at older geological sites, it was striking that those of us doing geology could see things that our colleagues could not. Our background allowed us to readily place a series of long-past events in chronological order, and to “see” those events in the context of other things happening around them. We could see how the small modern Souris River sits in a valley that was eroded by much larger floods from the outflow of ice-dammed post-glacial lakes; high in the valley wall, those flows had cut through sediment deposited previously by a glacier, which had itself transported materials from the Cretaceous shales that sit lower in the valley. We could recognize this sequence, and we could keep the events and their locations in order in our heads; from their comments, our non-geologist colleagues clearly had a difficult time with this.

During many summers I have done fieldwork in the Churchill area of the Hudson Bay Lowland, and in 2014 and 2015 I worked there with groups of geologists that included people far outside my area of expertise. I am an invertebrate paleontologist, but these field parties included regional stratigraphers, sedimentologists, a petroleum geologist, and a Quaternary geologist. We certainly did not understand the details and technical terminology associated with one another’s specialties, but we all seemed to readily follow the other people’s thinking and arguments.

I have taken part in many other geological field trips, and geologists never really seem to have trouble crossing boundaries between one specialty and another. It seems that, at some point, most geologists have learned to apply similar logical thinking to a variety of geological settings and subjects (and this even holds true for those of us who started off in disciplines other than geology). The fact is that we all share a set of general principles: the geological time scale, uniformitarianism, the rock cycle, erosion, weathering, the law of superposition, the law of original horizontality, and the application of Occam’s Razor to our field observations. Walking around in the world, we all carry this basic information as a toolkit, and as a result we can see what other geologists are talking about, whether they are structural geologists, paleontologists, or geophysicists.

Dave Rudkin of the Royal Ontario Museum acts as polar bear guard for a group of geologists at Bird Cove, Churchill, Manitoba: August, 2015.

Field experience is absolutely critical to this understanding. At some stage we have all had to consider the world as a four-dimensional place; we look at the three physical dimensions of each geological site, considering what we can see on the surface and interpreting how it is likely to extend below that surface, but we are also constantly interpreting the changes through deep time that have produced what we see today. We visualize how overlying or crosscutting features can be teased apart to find the likeliest story. Basic geological field research, considering a variety of rocks and settings, gives all of us at least a modest understanding of the breadth of geology. It emphasizes to us that basic principles are important, and it encourages our interest to such an extent that many of those principles become fixed in our brains.

I am, however, concerned that geology is in some danger of losing that breadth. We hear so often now that we need to be teaching students to do very specific tasks, so that they will be trained for particular technical jobs – they need to know how to use very complicated and specialized equipment, how to log core in certain standard ways, how to carry out standardized studies that lead to particular defined research goals. This is important – there is no question that people need to make money and have careers, that our economy requires skilled and talented scientists, and that we constantly have a need for particular resources or that certain sorts of environmental problems must be solved.

Using complicated or specialized equipment: me with a quarry truck, which we had contracted for some “serious collecting” near Churchill, Manitoba: August, 2016.

The danger in becoming an entirely “job-trained” modern discipline, though, is that we could also lose the vision that might allow us to solve future problems that we don’t yet even recognize. And the pursuit of very applied and directed work is likely to mean that scientists ignore anything they observe that was not included in the original workplan or grant proposal.

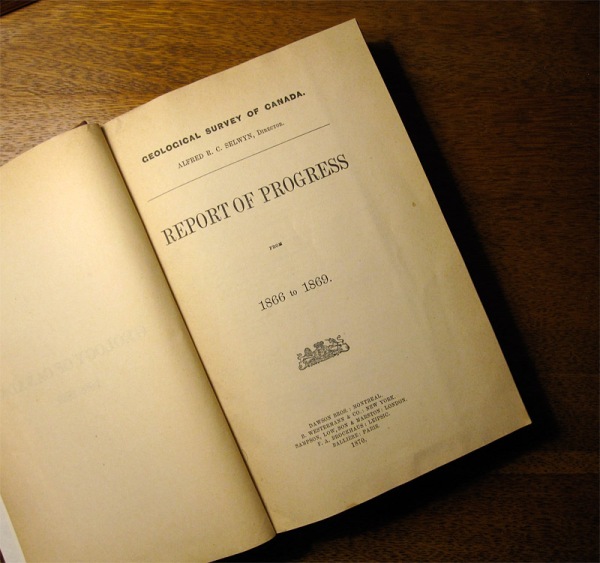

Lately, I have been reading some of the Geological Survey of Canada Reports of Progress that documented 19th century scientific exploration of Canada (I could say geological exploration, but many of them are so much more than that). Almost every field scientist employed by the GSC seems to have been a talented polymath, and as they carried out fieldwork in previously unexplored territory, they didn’t just look at geology. They observed and tried to understand everything, making incisive and generally accurate interpretations on the fly while canoeing many miles a day through often-hostile wilderness, collecting samples, mapping, and sometimes producing landscape paintings or photographs before sleeping under canvas. And then they did it all again the next day, and the day after, through the entire summer, perhaps making it back to “civilization” after the first snows of autumn.

Those GSC scientists were, of course, given the task of locating and documenting deposits that might have economic importance. In the report for 1869, for instance, Robert Bell assessed silver resources along Lake Superior and Lake Nipigon, Ontario (Bell 1870), and Charles Robb noted molybdenum deposits in central New Brunswick, an area where mine projects are still being developed today (Robb 1870). While they were doing this, they also considered other questions they had been assigned, such as Bell’s discussion of where the transcontinental railway might be located in the area around Nipigon.

At the same time, the GSC field geologists documented many phenomena that had no obvious economic significance, simply because they were there and might become important in the future. The remarkable reports of J. B. Tyrrell hold many examples of this, such as his description of the Cedar Lake amber locality in Manitoba (Tyrrell 1892). Bell (1880) and Tyrrell (1897) both considered glacial geology as they spent time in the area around Churchill, Manitoba; this topic was far from most of their other geological work, but both made significant contributions to the development of ideas on postglacial rebound.

These 19th century GSC geologists showed such remarkable drive, ability, stamina, and creativity, that most of us in the modern world are really just faint shadows by comparison. We may not be able to duplicate their energy, and the administrative and bureaucratic demands of the modern scientific world mean that we will never be permitted to have their focus, but we can still emulate their broad curiosity about all of geology and related disciplines.

As a museum curator, I feel very fortunate that many geologists do maintain this broad view of the world, since so much material in museum collections has come from such scientists. For example, a mining company geologist working with a drill crew in the Grand Rapids Upland was looking for an ore body, but was also interested in regional geology. I cannot speculate on what they found in terms of nickel and other metals, but he made an important paleontological find: he generously passed along to my colleague at the Manitoba Geological Survey that there were eurypterids (sea scorpions) in the Ordovician rocks in this area, and she in turn passed that along to me. As a result, we were able to go and scout in that same area, finding the site that hosts the strange and significant William Lake biota (Young et al. 2012).

Debbie Thompson (R) and me, carrying out paleontological field research at Airport Cove near Churchill: August, 2016 (photo © Michael Cuggy).

As we travel around our country and the world, it is incumbent on us as geologists to always be using those tools that our training has given us. If it is my job to search for fossils, that doesn’t mean that I should be ignoring folds or minerals, just as a mining company geologist should not ignore the landforms beneath which an ore body might lurk. There are never enough of us in any one discipline in this huge land, and we all benefit if we are each considering the entire science as we travel around, not just our own little piece of it.

As a science, we always need to collaborate, to think of our colleagues, make use of our networks, and pass along any information that could be useful to someone else. This is, of course, a major reason why the GAC exists, and why our annual GAC-MAC meetings are so critical to the continued health of our science in this immense country. The geological integration of time and space is our super power. Let us use it wisely!

References

Bell, R. 1870. Report of Mr. Robert Bell on Lakes Superior and Nipigon. Geological Survey of Canada, Report of Progress for 1866 to 1869, pp. 313-364.

Bell, R. 1880. Report on explorations of the Churchill and Nelson rivers and around God’s and Island lakes. Geological Survey of Canada, Report of Progress for 1878-79, pp. 1C-68C.

Robb, C. 1870. Report of Mr. Charles Robb on a part of New Brunswick. Geological Survey of Canada, Report of Progress for 1866 to 1869, pp. 173-209.

Tyrrell, J. B. 1892. Report on north-western Manitoba with portions of the adjacent districts of Assiniboia and Saskatchewan. Geological Survey of Canada, Annual Report, Volume 5, Part 1, pp. 1E-235E.

Tyrrell, J. B. 1897. Report on the Doobaunt, Kazan and Ferguson rivers and the north-west coast of Hudson Bay and on two overland routes from Hudson Bay to Lake Winnipeg. Geological Survey of Canada, Annual Report of 1896, Vol. IX, Part F, 243 pp.

*A version of this essay was originally published in Geolog (Vol. 45, No. 3, 2016), the quarterly newsletter of the Geological Association of Canada.

Hi Graham, nice to have you back, although it was nice to see a paleo in the GAC President’s chair for the 2nd time!

2 observations:

1) as a paleobotanist I have witnessed several times the different search behaviour on outcrop by myself vs. vertebrate and also invertebrate colleagues – we’re interested in different rock facies and our mental search images are quite different, so I miss those superb Eocene insects; it took a student trained in vertebrate paleo to find an Eocene hedgehog jaw at the Driftwood Canyon site in BC; and every ‘promising outcrop’ I took a mammal fossil specialist to in BC was ‘not quite right’, and when shown what was ‘ideal’, I must confess it was outcrop I would have never bothered to stop at.

2) as an Aussie, when I walk a trail with Canadian friends, they comment on my ‘eyes down’ walking style, vs. their ‘eyes front’ walking posture … keeping an eye out for bears. On a recent visit to Australia I walked a trail with my 2 brothers and just 5 mins into the trail our ‘eyes down’ walking habit was rewarded as I spotted a very poisonous brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis) sunning itself on the trail just where I was about to place my hiking boot!

Thanks, Dave. I hope we will have a chance to get together for a glass of wine in 2017!

Good to see you posting again. I’ve appreciated traveling and learning vicariously through your blogs.

Yes, it’s wonderful to explore with others who share a sense of awe in the universe and notice the beauty and its diverse life forms.

Thank you, Kate, for your kind comment!

This never goes away, does it? The ‘real world’ complains that we don’t teach student ‘real world skills’ so they are ‘unemployable’ (without additional ‘real world training’). But then, if we (=Academia) would change our ways completely, the ‘real world’ would complain that the graduates have no depth, can’t think out of the box etc. etc.

I have been there. When I was a young and starting Academic, I actually thought for a short while (maybe the first three years) that the ‘real world’ was right and that we should teach students more the skills that they were asking for. One of my Canadian Academic colleagues told me a few years ago “we just teach them to cook and that’s enough”.

Wrong – of course. ‘Real world’ in our case (the ‘real world’ of geologic practice) is usually the extracting industry and little or no innovation takes place there, especially not the last 25 years since industry outsources each and every job that isn’t routine. Benefits such as continued professional development have been shaved to the bare minimum and usually are the financial responsibility of young professionals themselves.

We should be giving students the broadest possible education with maximum intellectual depth and we should never demand less of them. It’s university, not trade school. If we do that well, they will enter the world as mature, independently and critically thinking professionals. Employers can train young professionals in the specific skills of the trade at their expense.

I guess I’ve been around too long

Thank you, Elisabeth. I agree with you – the ideal would, of course, be to give them both the broad framework and the technical skills, but I suspect that would take rather more than four years! And really, the principles are the key thing – without an understanding of those, they will never be able to really do geology.