What if This is the Stuff That Lasts?

Why do we spend time doing this sort of thing? Why would a person commit time week in, week out, to the process of blogging, patiently writing short pieces and editing photos so that they can be shared with anyone who might be interested, out there in the ether somewhere?

I suspect that there are many different reasons: maybe you find it a diversion, maybe you hope to develop an audience or market for your talents or products, maybe you just like connecting and communicating with other people. Regardless of your reasons, have you thought about how permanent this might or might not be?

If we talk about the permanence of blog posts, we tend to err on the side of worrying about losing these things. We hear about servers that crash, about data being lost forever, and I know of people who patiently archive everything they produce (yes, I should do that too, and I will . . . when I have the time . . . ).

But is it possible that the permanence of internet content might go the other way? Given the endlessly expanding storage capacity of computer networks, is there some probability that anything we post in this medium might still be available to the world in 50 years, or 100 years, or 1000 years? Is there any chance that the Internet will become like the great library of Alexandria, and that people in a strange far distant future will be able to read the words I am banging out right now?

That is a frightening thought. Being a scientist, there are things I write with the hope that they will be of interest or use to future generations: papers about how fossil corals grew, or the fossil record of jellyfish, or the description of a giant trilobite. Those papers can take many months to prepare, with each word considered and re-considered, each reference checked and re-checked. But what if it turns out that those things have no staying power and are lost, while these little random scrawls are my lasting legacy? Since none of us can predict the future, should we ponder and re-write every piece we post here?

Nah. Let’s just keep throwing stuff at this virtual wall, and see what sticks.

© Graham Young, 2012

The graffiti are courtesy of the folks who have left their marks on the Grand Rapids Uplands and Cormorant Hill roadcuts.

Depositional Hiatus

I realize that the posts here have been a bit sparse in the past month or so; in addition to the fieldwork mentioned in my last piece, we have also been a bit busy at the museum. Installation of our new mineral exhibit last week was all-consuming and occasionally hairy, but we are delighted with the results! If you are interested, you can see some images of the exhibit here.

New posts are in the works …

Burrows on Burrows

Ordovician Thalassinoides in the Grand Rapids Uplands, Manitoba

Thalassinoides covers a glacially-polished horizontal surface in the Grand Rapids Uplands (scale bar is in centimetres).

The concept of trace fossils is probably somewhat foreign to most people. People may not think often about preserved evidence of ancient biological activity, but many are quite familiar with certain sorts of tracks and traces. If you live in southern Manitoba or have visited buildings such as the Canadian Parliament Buildings in Ottawa, you will have seen the trace fossils that give the Ordovician Tyndall Stone (Red River Formation, Selkirk, Member) its characteristic mottled or “tapestry stone” appearance. These mottles are actually the branched boxworks of preserved burrows, often assigned to the ichnogenus Thalassinoides.

Ordovician Thalassinoides often occurs in rocks deposited on well-oxygenated normal marine seafloors, commonly associated with body fossils. The mottles of this bed-parallel Tyndall Stone slab, photographed at the Garson Quarries, occur with a horn coral (lower left), gastropod (snail, centre left), and cephalopod and gastropod (upper left). The dark dolomitic burrow mottles are very obvious against the surrounding limestone (calcite) matrix. The lens cap diameter is 56 mm.

The beautiful mottling of Tyndall Stone demonstrates the existence of tremendous numbers of organisms burrowing into an ancient seafloor. Although the Thalassinoides in this stone is impressive, it is certainly far from its only occurrence in the rocks of Manitoba. Revisiting sites in the Grand Rapids Uplands last week, I had the chance to photograph stone at one locality where it contains burrows even more abundant than those seen anywhere in Tyndall Stone. Not only are they abundant, but their preservation is such that the surrounding stone weathers away in places, leaving a near three-dimensional meshwork of burrows visible on the rock’s surface!

This glacially polished surface in the Grand Rapids Uplands has been somewhat weathered, and the burrows are beginning to stand out in three dimensions.

This remarkable exposure, some 500 kilometres north of Winnipeg, is part of the Gunton Member of the Stony Mountain Formation (Upper Ordovician, upper Katian, about 445-447 million years old). It is a bit younger than Tyndall Stone, but still within the same period of geological time. The rock is exposed on broad open surfaces that had been scraped smooth by the Ice Age glaciers, and more recently “re-cleaned” by bulldozers during development of the hydro and highway rights-of-way. In the years since that last human work was done, they have been gently washed by the rain, and somewhat less gently weathered by the cold season’s frosts.

When we first visited this place in about 2004, many of the bedding plane surfaces had already been broken up and had begun to turn into a plain of gravel. We feared that the beautiful burrows would soon be lost to science, and returning this year I was afraid that there would be no bedrock left to observe.

The rock is, however, tougher than that. Right now some of the surfaces are at the optimal stage of weathering: the slightly softer dolostone around and between many of the burrows has been removed, leaving the burrows standing in beautiful three-dimensional relief. The weathering has progressed so far in some instances that you can see down between burrows to those in the layer beneath. Sadly though, some surfaces have progressed past this point, and are spalling off to the extent that they are better road fill than they are evidence of ancient life.

Gastropods such as this large Maclurina are among the body fossils occurring between burrow mottles.

But what teeming life do these immensely abundant burrows provide evidence of, anyway? The truth is that we don’t really know. Thalassinoides-type burrows in younger rocks were probably most often made by crustaceans such as thalassinid shrimp. These sorts of crustaceans are, however, not known as far back as the Ordovician, and it has been suggested that Ordovician burrows may have been made by asaphid trilobites. And maybe they were made by sea anemones or polychaete worms? There are still so many questions about the world for us to answer!

To read more on topics related to this post, you might want to look at some of the following:

Cherns, L., Wheeley, J.R., and Karis, L. 2006. Tunneling trilobites: habitual infaunalism in an Ordovician carbonate seafloor. Geology, 34: 657-660.

Coniglio, M., 1999. Manitoba’s Tyndall Stone. Wat on Earth: Waterloo University Earth Sciences Newsletter, Spring 1999, p. 15-18.

Gingras, M.K., Pemberton, S.G., Muehlenbachs, K., and Machel, H. 2004. Conceptual models for burrow-related, selective dolomitization with textural and isotopic evidence from the Tyndall Stone, Canada. Geobiology, 2: 21-30.

Kendall, A.C. 1977. Origin of dolomite mottling in Ordovician limestones from Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology, 25: 480-504.

Young, G.A., Elias, R.J., Wong, S., and Dobrzanski, E.P. 2008. Upper Ordovician Rocks and Fossils in Southern Manitoba. Canadian Paleontology Conference, Field Trip Guidebook No. 13, CPC-2008 Winnipeg, The Manitoba Museum, 19-21 September 2008, 97 p.

© Graham Young, 2012

18th Century Graffiti at Churchill

George Holt was sailor and mate of the trading sloop Churchill (information for this and subsequent captions is from Lorraine Brandson’s book, Churchill Hudson Bay: A Guide to Natural and Cultural Heritage).

We first came upon Sloop Cove almost by accident. We had heard of it, mostly because of Samuel Hearne’s much-photographed signature carved into the quartzite. We knew roughly where it was across the estuary from Churchill, but we had no intention of visiting it when the helicopter dropped us off at the back of the beach one gloomy summer afternoon in 2001. After all, we were seeking fossil sites, not historic ones.

Nevertheless, as we trudged across the rock and moss that lay between us and the likely location of some interesting outcrops, we came upon this long cleft that ran back from the river into the side of the quartzite slope. A pool of water lay in the bottom of the little valley. The rusted chain fence showed that this was an important place, since in general not much is marked or labelled in the Lowlands. Then we saw what the fence was protecting: scratched into the quartzite were many signatures and other markings from the early fur trade days, not just Hearne’s!

The great majority of these date from the mid 18th century, with a smattering of more recent examples (it appears that Parks Canada removes anything added nowadays, though). But why are they here? And why did these men spend so much time laboriously carving into this famously hard and tough stone?

The glacially polished quartzite surface is decorated with abundant graffiti, including quite a bit that is difficult to see unless you get the angle just right.

William Davisson was a sailor who spent two years at the Churchill Hudson’s Bay Company trading post. (photo © Dave Rudkin, Royal Ontario Museum)

The answer lies in the use to which the cove was put in those early historical times. Although we like to think of land as stable and solid, the Hudson Bay Lowlands have been rising ever since the removal of a huge weight of glacial ice a few thousand years ago. Various estimates have been made for the Churchill area, but it is most likely that the river mouth has been rising about one metre per century, and as a result Sloop Cove has risen two metres plus since the 1750s (a pdf showing detailed analysis can be found here).

Furnace and Discovery were small Royal Navy ships (bomb ketches) that spent the winter of 1741-42 at Sloop Cove during an unsuccessful search for the Northwest Passage.

George Holt’s mark and the surrounding graffiti. On the upper left is the “hanged man.” The tale is that John Kelley was hanged for stealing a goose, but there is apparently no documentation of this event. (photo © Dave Rudkin, Royal Ontario Museum)

Back then, the bottom of the cove was probably flooded by salt water at very high tides, and in any case it was close enough to sea level that small ships (sloops) could be hauled out there. Of course this may have been done for maintenance, but most importantly this was the first really protected spot upriver from the Prince of Wales’ Fort, and it was essential to get boats out of the river in winter so that they were not subject to ice damage.

Even now the sea ice at Churchill can remain well into the time that southerners think of as “summer”, and as a result the men waiting to re-launch their little ships would have had many days of warm weather before they could set sail. What better way to pass the sunny hours than to leave your mark on the stone? Permanently, as it turned out.

With fossils to be found down the shore, we had far less time on our hands and took some quick photos before tramping off toward the strandline. We wondered about the stories behind some of these marks, but in 2001 there did not seem to be all that much information available. Recently there has been some wonderful explanation by Lorraine Brandson in her excellent guide to Churchill. And online there are various resources, including this photographic documentation of the entire set.

In this view down the estuary from near Sloop Cove, the stone Prince of Wales’ Fort can be seen as the low structure on the right horizon.

© Graham Young, 2012, with thanks to Dave Rudkin for permitting me to use so many of his images!

The Museum Writ Small

Walking through the Centre Pompidou, my attention was drawn by this small museum box by Joseph Cornell. I find it deeply satisfying that, among his many boxes, this surrealist created a “museum” in which all things in the universe could apparently be contained in a few little vials.

Deeply satisfying . . . and yet . . . not. Artistic attempts to represent and define the natural world so often remind me of certain religious rituals, or at their extreme, of a cargo cult. It is sufficient to say something, even if the speaker has no understanding of what the words might mean. But maybe the museum box is intended to be antithetical to the logical structure of the natural history museum, and maybe it is best to enjoy all museums without too much conscious consideration.

Is it the museum writ small and yet ridiculous? While we are on the subject of entering realms of which the interpreter has but a meagre understanding, at the Centre Pompidou my daughter and I became taken with the idea of photographing bits of the building as though they were abstract works of art . . .

© Graham Young, 2012

Remotely Similar

Coastal mangrove in the Florida Keys lives in an environment roughly comparable to that in which the rocks at William Lake were deposited, though of course mangrove had not yet evolved in the Ordovician. (this photo, and all the other scanned slides, are by the late Frank Beales or by students or colleagues from his Florida fieldtrips, taken between the 1960s and 1981)

Following my last post about remarkable juxtapositions of ancient and modern analogues, I realized last week that the converse or opposite is also more common than might be supposed. Appropriate modern analogues are often located an immense distance from the ancient deposits to which they are similar. Since some of us tend to study rocks that are near where we live, this means that we would need to travel thousands of kilometres to see similar modern examples.

For this, we can blame (or thank) the combined effects of time, plate tectonics, and climate change. If you are able to stand in one place for long enough – a few hundred million years should suffice – then eventually that place will be nowhere near where it was when you started standing. You have not moved, but the continents and seas have moved around you.

Collecting at the William Lake site in summer, 2010. L-R are me (foreground), Michael Cuggy, Sean Robson, Matt Demski, and Debbie Thompson. (photo © Dave Rudkin, Royal Ontario Museum)

I had this thought as I repetitively ground specimens in the lab. These were little bits of mudstone that had started off as fine carbonate sediment on an immense tropical tidal flat or mudbank some 445 million year ago. This shallow water environment was somewhere just south of the equator, in a large sea that covered the middle of the ancient continent of Laurentia. Over time the mud was buried under other sediment and became rock, and the sea went away to be replaced by land. Laurentia continued to move ever so slowly, bumping up against the other landmasses 300 million years ago to form the supercontinent of Pangaea. When Pangaea rifted apart 100 million years later, most of Laurentia became most of North America, moving northwestward and leaving a widening Atlantic Ocean in its wake.

After all those travels, part of that ancient coastal mudflat eventually became the William Lake site, situated now in a boreal forest in the middle of a northern continent, where it is alternately frozen for six months of the year and infested with blackflies and mosquitoes for the other six months. We go to William Lake to collect the wonderful fossils of creatures that died on that mudflat, but there is nowhere nearby that we can see comparative examples, either for the creatures or for their environment.

A modern analogue for William Lake? The tranquil surface of Florida Bay is interrupted by an extensive mudbank.

Considering the creatures this is, perhaps, less of an issue. Some of them, such as the eurypterids (“sea scorpions”), have no close living relatives. For others, such as the jellyfish, I can study a great variety of preserved specimens for the price of an air ticket to the collections in Ottawa or Toronto.

Or, in some cases, I can simply order preserved specimens from a biological company that supplies schools and colleges. On several occasions I have buried dead jellyfish or other gelatinous zooplankton in wet lime mud, exhuming them for study after the mud had dried and hardened. This may appear comical or strange, but it has turned out to be critical – these creatures have so little tissue, relative to the water they contain, that their appearance changes dramatically as they are compressed and dried out. By carrying out these crude experiments, I have been able to make sense of some very odd fossils.

Air-breathing mangrove roots and a microbial crust, in the supratidal or upper intertidal zone of Florida Bay

But what of the rocks themselves? We have been collecting at William Lake for just about a decade, systematically peeling back the rocks bed by bed and layer by layer. Now that we have collected much of the succession of units, we are trying to understand how they relate to changing ancient environments. We have been polishing sections through each bed, looking at the fine details that show ancient ripple marks, channels, and mud pebbles.

As I examine these, I find that I am spending more and more time reading the scientific literature on similar environments in the modern day. But so often, I find that a paper will only give me a little bit of the information I seek. Just as publications on modern jellyfish don’t really tell me what I need to know about jellyfish fossils, the papers on modern sedimentation do not really answer my questions about William Lake. After all, the authors of those papers were doing research to answer their questions, not mine!

A cut through the supratidal sediment reveals layering below the surficial microbial mat. We see very similar features in the rock at William Lake.

I suspect that the answers I need will only come from first-hand examination of modern carbonate tidal flats and mudbanks. I last looked at such places on a wonderful Florida Keys fieldtrip from the University of Toronto, led by the inimitable* Dr. Frank Beales in 1981. Frank’s trip was one of the best experiences of my life, but it was long ago, I was an ignorant student, and my memories of it are as faded and washed out as the slides I have scanned to illustrate this piece.

So it is beginning to look as though I will have to travel to study somewhere warm, coastal, and muddy, preferably in the company of a sedimentologist as accomplished as Frank was. I should go either to South Florida, or (even better) the Bahamas, or maybe the Persian Gulf. But how can I possibly explain to a granting agency that I really need a few weeks in the Bahamas, without making it seem as though I just want a jolly jaunt to escape the Winnipeg winter? Complications, complications.

This photo taken just after a hurricane (Hurricane Betsy of 1965?) shows how the surface of the supratidal zone can be flooded periodically.

The intrepid Professor Beales on the edge of one of the Florida Bay islands. During our trip, Frank appeared to undergo an amazing transformation, from an elderly tweed-wearing British professor to a dynamic, fit, energized, entertaining field scientist who needed no sleep. I’m sure this was his natural element, and of course though he seemed aged to the students, he wasn’t really old at all (just a few years older than I am now, actually!).

Our group of U of T students, hamming it up on the dry rocks off Key Largo in fall of 1981 (I am the lanky black-haired guy on the far left).

Since so much time has passed since these photos were taken, and since most of them were Frank’s and I don’t have a clue who took the others, I have not requested permission to reproduce these images. If any of them happen to be yours, I would be delighted to give you credit, or to add your name if you are one of the other students in the class photo!

* Actually, we did used to imitate Frank. He was a supremely knowledgeable sedimentologist, an excellent raconteur, and a wonderfully kind and patient teacher. In class, however, he tended to lose his train of thought, and his long pauses and drawn out open-mouthed “uhhhhhh”s were legendary (and perfect targets of imitation for the insensitive young students we were then).

Adjacent Analogues

Sedimentary geologists, with our uniformitarian approach to the world, often look for modern environmental analogues that might help us to better understand the ancient deposits we study. Where they occur in close physical conjunction, the modern can inspire scientists analyzing the ancient. Although these sorts of things may well occur often, I can’t seem to find an existing term that describes this phenomenon. I propose that we call them adjacent analogues.

I started thinking about these things a couple of weeks ago, when I was visiting Fredericton. My brother and I were walking along the north side Green, and I got taken with photographing the abundant driftwood left along the shore by recent high water. The Saint John is a large river, and in full flow it can move substantial objects. In some places, there were even clumps of worn and abraded trees, still attached by their roots.

Turning from the shore, my attention was drawn by large blocks of stone that had been placed to separate the boat launch area from the lawns. Many of these consisted of relatively monotonous sandstone, but one of the boulders closest to the water appeared to have more varied features. Crouching to examine it closely, I could see large chunks of well-preserved ancient wood, much of it still consisting of organic material, surrounded by debris and rusty stains. The sandstone blocks appeared to be consistent with Carboniferous (Mississippian to Pennsylvanian) deposits that make up much of the bedrock in the Fredericton area, so this fossil wood was in the range of 320 million years old (see Whitehead, 2001, for an outline of Fredericton area geology; a pdf can be found here).

The boulder (above) and a detail of the wood (below). The brilliant white circle is a Canadian quarter (diameter 24 mm) reflecting the sun.

Then it struck me: here I was, surrounded by driftwood on the bank of a large river, and the rock sitting on the bank just happened to contain ancient driftwood that had been deposited under similar conditions hundreds of millions of years ago. The ancient and modern in immediate conjunction! Worlds in worlds, wheels in wheels!

Of course, if we compare them in more detail, there are significant differences. The Saint John at Fredericton flows out of gentle hills and meanders broadly; most sediment along its banks is well-weathered and silty. The Carboniferous sandstones, on the other hand, were apparently deposited in alluvial fan conditions and contain quartz grains mixed with rock fragments suggesting that the material had not been transported a huge distance. Still, as an illustration the comparison was striking.

In this quarry at the top of the hill on the south side of Fredericton, cross-bedded rust-stained sandstones can be observed in place.

Such adjacent analogues must occur in many places. There are huge areas where modern rivers cut through ancient floodplain sediments; excellent examples can be seen in various places in western Canada. Similarly, in the Churchill area of Manitoba the famous Ordovician rocky boulder shoreline occurs in conjunction with a modern rocky shore, and deposits representing an ancient tropical cove occur within a modern subarctic one.

Perhaps one of the strangest examples I can think of readily is at Kuppen in Gotland, Sweden, where Silurian sea stacks and other rocky shore features occur close to sea stacks along a modern shore (see Fig. 3 in this pdf; note that it is a large file).

My brother’s cellphone photo suggests that I may appear a bit eccentric when I get interested in looking at rocks. Note the huge quantity of driftwood beside the boulder. (photo by Chris Young)

The scientists working at such field locations cannot help but be inspired by the modern environments that surround them. Of course we must be cautious in applying modern observations to long-gone paleoenvironments, but they can certainly provide us with valuable insights and give us ideas that we might never have if we only saw the two in separate places and at separate times.

Adjacent analogues also serve as wonderful examples for field trips by students, professionals, and interested amateurs. It would be great to compile a list of such places; if you know of other good examples, please send them to me and I will try to do another post on this topic!

© Graham Young, 2012

Modern Shore: Lincoln Eve

Meeting a delayed plane this evening, I discovered I had an extra 15 minutes to kill. Almost anywhere else I would have wandered around the airport, maybe bought a coffee, but I am in Fredericton and there are other options here. Five minutes from the airport, the river was gorgeous and there remained enough vestiges of light that I could hope for photographs. A set of fortunate coincidences!

The valley is very grand; this is really the beginning of the lower Saint John floodplain, with its flat treed islands, back swamps, and yazoo tributaries. The broad river in semi-flood produces serene reflections of the late evening clouds. Just up the road, the century-old Wilmot Bluff lighthouse now nestles semi-hidden in the trees, looking more than a bit pagoda-like. Long retired from active use, perhaps it saw enough of the river during its working life.

As I snap my last crooked photo, I hear the roar of the inbound turboprop as it slows on the runway a kilometre or two away. A signal that it is time, sadly, to head back to the modern world.

© Graham Young, 2012

Modern Shore: Images of Decay

The Island of Saaremaa, Estonia, 2007

There are places where decay of both natural and man-made materials seems to be concentrated in great variety. The coast of the island of Saaremaa is one such place. I find that decay often makes for beautiful forms; I only wish that I had thought to take more photographs!

In a quiet bay, a dried mat of seaweed on the shore is accompanied, below sea level, by a rim of repulsive purple sulfur bacteria. The mat is cracked polygonally, and the seaweeds have been compacted and rendered into a dense amorphous material.

© Graham Young, 2012

Illness of a Friend

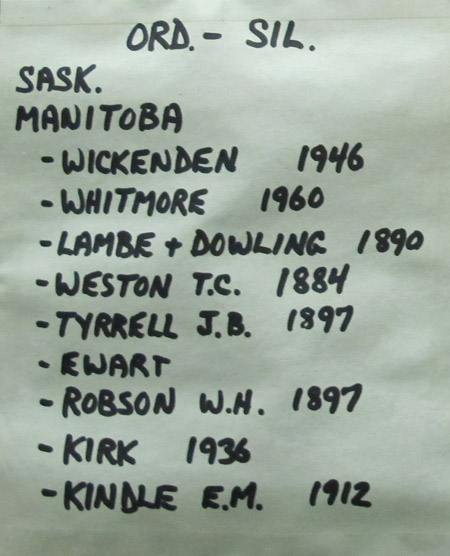

Hand-labelled nineteenth century specimen boxes record early scientific expeditions to the Lake Winnipeg area.

I just heard this week that a friend is very ill. This friend has not been “in robust health” for a quite some time, but still had been managing in an “I’m alright, really” sort of way. Now it seems that there has been a sudden turn for the worse, and I am fearful about my friend’s future. We have not heard anything about it being terminal, but still, the prognosis is far from favourable.

This news has made me think about our relationship; I guess I have tended to take this friend too much for granted. But we have had such conversations in the many happy hours we have spent together … such wonderful conversations! For you see, my friend is very old, quite remarkably old. My friend has memories going all the way back to the 1840s, back to a time before there was even a country of Canada. And since those memories started, my friend has been everywhere across the northern half of this continent. Literally everywhere, to many places I have not even heard of. And every place holds some special precise recollection of our nation’s distant and historic pasts. I have listened carefully while my friend has told me about the life forms of ancient tropical seas, and about the almost superhuman scientists who traversed this country before the days of paved roads and airplanes.

Long before we visited Inmost Island, the GSC's intrepid T.C. Weston had been there! This is an Ordovician alga (seaweed).

I’m sure you are more than aware by now that the friend I write of is not human. This friend is a collection, the National Type Fossil Collection and the bulk fossil collections of the Geological Survey of Canada. This collection is one of the most remarkable and little-known institutions of this country: a huge assemblage of fossils that has been built up through the work of many superb scientists over the past 170 years or so! It not only represents a physical record of geological field research in this country and a reference for those wishing to understand past work; it is also a fantastic resource for scientists, both at present and in the future. This collection forms an immense body of raw material for scientific study, painstakingly assembled at what would be, cumulatively, a tremendous cost.

I worry about this collection because news has just come down that the Federal Government’s current round of budget cuts will be affecting its curatorial staffing. And that is a serious concern. Certainly much of the collection is in good shape, so perhaps it may look to some managers as though they should be able to just close the door, opening it occasionally to allow access to trusted scientists. But a collection is a living, breathing organism that requires constant care and feeding; you cannot simply assume that it will be fine on its own for a while. It will deteriorate: specimens will become separated from their labels, boxes will fall apart, entries in the catalogue may no longer have corresponding fossils in the drawers. Without care over a longer term it might become useless, a candidate for the Ottawa landfills.

This collection has been built on trust, with each generation’s new collections being added to the existing body, and all of it passed down to the future. At a time when our government is focused on the discovery of new resources, and when biostratigraphy (the time -significance of fossils) is useful for finding really practical things like sediment-hosted base metal deposits, it would be extremely sad to see this wonderful reference library of geological objects fall slow victim to entropy, dermestids, and decay.